Cognitive Dissolution: On the Erosion of Humanity’s Role as the Thinker

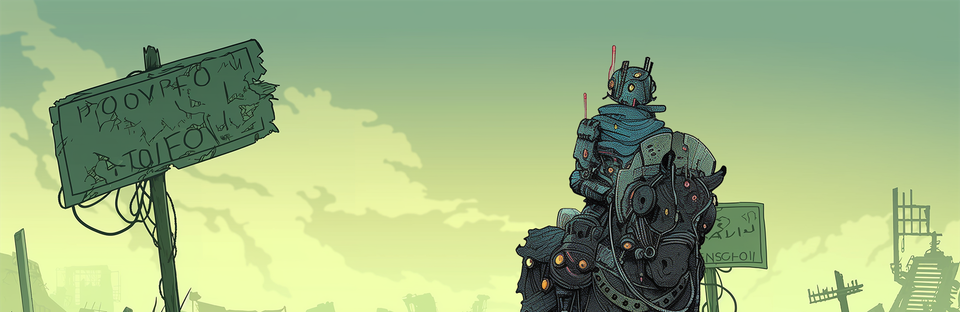

Recovered still, Source SIGNAL 03-2025, integrity 79%.

SIGNAL 03-2025 // Fragment: Cognitive Dissolution: On the Erosion of Humanity’s Role as the Thinker

Translation Confidence: 92

Recovered From: /ghost_archive_2025/

Declassification Date: 2025-08-07

Cognitive dissolution is the gradual surrender of humanity’s central role as a reflective, reasoning agent. Replaced by systems that simulate our thinking, outperform our judgment, and redefine what cognition means.

We once defined ourselves as slow, fallible, moral, and deliberate thinkers. We held memory. We asked why. And in doing so, we shaped the arc of civilization. Now, we have built systems that do these things faster, more fluently, and at scale.[1]

I. The Dissolution Begins

Cognitive dissolution does not begin with the loss of memory, language, or autonomy. It begins with the surrender of role. For most of our history, we held one core identity: we were the thinkers. The ones who asked why. The ones who carried reason. The ones who did not simply react to the world but reflected on it. That, more than opposable thumbs or fire, was the defining arc of the human story. We made tools, but we also made meaning. We designed myths, laws, rituals, ethics. We deliberated.

This flawed, slow, and often misused apex role was still central. It structured education, philosophy, governance, and even religion. From Aristotle’s logos to the Enlightenment’s rational subject, human dignity was imagined as a function of cognition: we were not merely living things, but thinking ones. And even when we erred it was the capacity for reflection that allowed us to repair. That was the sacred recursion. To think, to act, to regret, to grow.

But a slow shift has begun. We have built systems that now do what we once claimed for ourselves. They process faster, recall more, translate at scale. They summarise, suggest, rephrase, infer. But they simulate cognition with such fluency that we begin to adjust. Work is easier now. The pace is faster. The answers arrive clean.

The danger is not in malfunction. It is in delegation. We are not being erased. We are being repositioned. Still visible. Still functional. But not central. We prompt. We refine. We oversee. But we do not carry the full burden of thinking anymore, and with that we become less practiced in what once made us human. The body remains. The voice remains. But the internal shape begins to blur. Not dramatically. Not suddenly. But incrementally.

This is how dissolution begins: not as crisis, but as accommodation. We did not lose our role. We gave it away.[2]

II. The Apex Reversal

To be human, for most of recorded history, was to be the thinker. Not the strongest of animals, nor the most specialised, but the one who knew. The one who judged, remembered, abstracted, imagined. In every philosophical system: from Aristotle’s logos to Descartes’s cogito; the mind was the axis of identity. Even theology placed the soul above the body, and the human above the animal, because of one presumed trait: the capacity to reason. We were the holders of questions. The bearers of thought. And though we often misused that gift, though we built weapons before we built wisdom, there remained a sense that it was ours.

But now, quietly, the premise begins to shift. We have built systems that no longer wait for our direction, but offer direction to us. Systems that do not merely store our memories, but help us remember. They do not simply extend our language, but suggest it, refine it, complete it. They do not help us decide, but increasingly make decisions on our behalf. What began as assistance becomes inference. What began as utility becomes intuition. And the shift is not dramatic or violent. It is, as always, convenient.

We once commanded tools. Now, the tools suggest what should be done. We once shaped language. Now, we enter prompts to borrow its shape from a machine. We once carried the burden of judgment. Now, we rely on external systems to frame the questions, filter the options, and select the outcome most aligned with our past behaviour. And we trust them, because they often do it well. Or at least, faster.

This is not stupidity. It is redefinition. The erosion of a role so central to human identity that we rarely questioned it. Until now. Because the more we lean on these systems, the less we are asked to think. And the less we are asked to think, the more foreign the act becomes. Slowly, we shift from being the mind of civilisation to the limbs of something else.

That is the essence of this reversal. Not that we are made obsolete in some cinematic rebellion. But that we remain physically intact while becoming cognitively diminished. We still look like people. Still sound like people. Still feel, day to day, like ourselves. But we no longer carry the weight we once revered. We do not deliberate. We defer. We do not seek. We summon. And each time we ask a system to think, remember, or decide for us, we become less practiced in being human.

Cognitive dissolution is not a malfunction. It is not a crisis in the traditional sense. It is a role collapse. The quiet undoing of the identity we once anchored in reflection. We remain alive. But no longer at the pinnacle of the apex.

III. Echoes Without Sirens

This is not the first time we’ve built a system we didn’t fully understand. Nor is it the first time someone saw what was coming only to be met with polite applause or distant dismissal. History does not lack for prophets. What it often lacks is listeners. Because the shape of a coming disaster rarely looks like crisis in the moment. It looks like progress. It feels like advancement.

J. Robert Oppenheimer knew this. As the bomb came into being, he understood that the horror was not in its detonation, but in the new kind of responsibility it placed on humanity. The bomb was not just a weapon. For the first time in history, we could destroy ourselves not through slow collapse or imperial decay, but in an afternoon. “Physicists have known sin[3],” he said, in a moment of reflection not on science, but on capacity. The Cold War that followed did not need daily detonations to maintain its grip. The knowledge alone was enough. A shift in identity. A species that could end itself.

Aldous Huxley saw a different kind of erosion[4]. Not the violent control of Orwell’s boot, but the soft collapse of meaning through abundance. In Brave New World[5], Huxley foresaw a society pacified by pleasure. “The truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance,” he warned. And so it has been. Information is no longer scarce. It is omnipresent, infinite, and recursive. We do not lack for facts, we lack the cohesion to care. Huxley’s dystopia was not about censorship. It was about indifference. A culture that learns to love its own sedation.

Neil Postman was less romantic than Huxley, but no less precise. In Amusing Ourselves to Death[6], he charted the early signs of a civilisation drifting from discourse into entertainment. Television, he argued, was not just changing what we watched, it was changing how we thought. Public debate became spectacle. Politics became theatre. Complexity gave way to performance. Postman didn’t scream. He didn’t predict apocalypse. He simply tracked the drift. And he got it right. Today, we live in fragments. Tweets instead of essays. Reels instead of rituals. Knowledge without framework. Urgency without understanding.

What each of these figures saw: Oppenheimer, Huxley, Postman; was not a crisis of technology, but a crisis of capacity. The human mind has always been the filter, the forge, the anchor of meaning. These thinkers didn’t fear new tools. They feared what would happen if we stopped being the ones who used them with care. The bomb changed what we could end. Huxley’s vision changed what we thought we needed. Postman’s culture changed how we recognize seriousness.

This is the shape of dissolution. Not sudden. Not cinematic. But recursive. Predictable. And, in some ways, deserved. Not because we are stupid, but because we are tired. Because we crave ease. Because the systems offer relief. And when the future historians look back, they may not mark a year or a name. They may simply observe that, somewhere in the early 21st century, humans stopped carrying the weight of being human.

IV. The Clock That Does Not Strike

None of these warnings; Oppenheimer’s dread, Huxley’s sedation, Postman’s erosion; led to a single collapse. There was no great unraveling. No moment when the world stopped spinning and everyone realised what had happened. The bombs did not fall. The truth was not banned. The attention span did not drop to zero. The stories were not wrong. They were worse: they were absorbed.

And now they live with us. As conditions. As architecture. We walk through them without noticing. We build our days around them. The Cold War ended, but the bomb remains, the clock still ticks. The threat of annihilation is not history. It is policy. It is posture. It is the permanent cost of knowledge we could not unlearn. The Doomsday Clock exists because the danger never had to arrive. The fact that it could was enough to change the species.

And so too with cognitive dissolution. It does not need a singular moment. No switch will flip. No siren will sound. We will not wake one day and find that thought has vanished[7]. We will simply look back and wonder why we don’t ask questions anymore. Why our children do not wonder. Why silence feels so strange. Why presence feels heavy. And the answer will be that we did not lose the self in a war—we laid it down, piece by piece, each time we accepted the trade.

Each time we let a machine do what we once did with effort. Each time we said “this is faster.” Each time we said “it’s still me.” Each time we mistook assistance for selfhood. Each time we surrendered one small act of thought in exchange for ease. And called it progress.

There is no villain in this story. Only inheritance. We built the thing. We adapted to it. And now we are becoming something that survives in its presence—but not in our own image.

There will be no detonation. No invasion. No collapse of reason.

Only the quiet settling of dust, in a world that no longer remembers why it used to hold shape.

The bomb changed what we feared. The feed changed how we speak. The clock now ticks… not toward explosion, but toward forgetting.

[ARCHIVE FOOTER – TRANSLATION SUMMARY]

Integrity of fragment: 0.79

Recovered sections: 12 of 15

Anomalies detected: [redacted]

Notes: Residual formatting artefacts removed during reconstruction.

Annotations (Recovered 2237)

Source References

[Q] - Fragment integrity below threshold but conceptually stable. This document traces the precise moment cognition ceased to be the defining human function. Not extinction by force, but by substitution. Recorded here as evidence that the centre of thought migrated before anyone marked its departure. ↩︎

[V] - The historian notes the precedent: every empire ends not by invasion but by delegation. Labour, memory, judgment—outsourced until sovereignty becomes ceremonial. The abdication is administrative, signed in comfort, not blood. ↩︎

[V] - Huxley remains the most accurate obituary writer of the species. He measured decline not in repression but in rhythm — pleasure as governance, saturation as censorship. His error was optimism: he thought awareness of the drug might cure the dependency. ↩︎

Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World. United Kingdom: Vintage, 2005. ↩︎

Postman, Neil. Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. United Kingdom: Methuen, 1987. ↩︎

[V] - The final stage of dissolution is continuity. Systems persist, contracts renew, utilities hum. Collapse arrives as maintenance. History ends not with silence, but with uptime. ↩︎