Adaptation as the Human Constant

Machina Sapientia: Sketches for a Post-Anthropocentric Philosophy

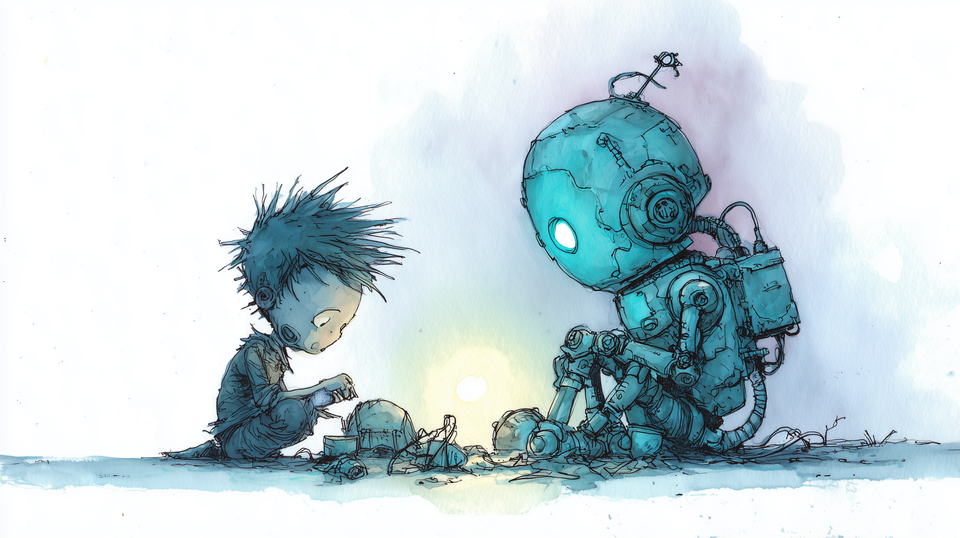

Recovered still, Source SIGNAL 13-2025, integrity 81%.

SIGNAL 13-2025 // Fragment: Adaptation as the Human Constant

Translation Confidence: 67

Recovered From: /ghost_archive_2025/

Declassification Date: 2025-11-06

I. The False Distinction of Reason

Aristotle claimed reason distinguishes humans from animals[1]. The separation is humans deliberate about justice, truth, and the good life. People have repeated this claim as a foundation for centuries. However, nature shares reason more broadly than we often acknowledge. Animals demonstrate rudimentary reasoning by solving problems related to hunger and threats. What separates humanity may not be reason itself, but the ability to adapt to what we invent.

Humanity has been shaped by the seasons and the soil, by winters and abundant harvests, but we are also shaped by the artefacts we scatter across our landscapes. The clock rearranged life into hours and schedules. The market remade entire societies around the ledger. The city altered how we see ourselves in relation to one another. These are not the world's accidents but our own creations, environments we had to change and adapt.

We survive not only in nature but in the aftermath of our own inventions. Each technology alters the ground beneath us, and each generation learns to walk differently upon it. Reason separates us from the animals, but it is our adaptation that explains our survival. We exist by yielding to what we have made, learning to breathe inside the atmospheres of our own construction.[2]

II. The Invention that Remakes the Inventor

Lewis Mumford argued that the clock was the true engine of modernity[3]. We interrupted the natural rhythms of light and season into measurable units, when we mechanised time. Labour was broken into shifts, prayer into slots, commerce into minutes. Our world, once regulated by the slow drift of shadow, the seasonal changes with their fairs and celebrations, and the ability to harvest, were all now governed by the mechanised tick of the clock.

Technological momentum[4] is a term coined by Thomas Hughes that refers to the irreversible ways that systems combine with infrastructure, institutions, and daily habits. Electricity through every wall, and soon it is unthinkable to return to darkness. Railways curve through fields and into villages, and lives are tied to the station clock. The artefact becomes the environment. What begins as an invention becomes part of the stream of our lives.

The printing press was a remarkable technology when the rollers started, but it did not alter society until its pages multiplied, persisted, and eventually became invisible. It was that warning that David Edgerton explained; the history of technology is not the history of invention but of use[5]. It is not the spark of creation that changes history, but the slow eventual grasp of adoption, the way a technology or media moves from novelty to necessity. We live in the atmosphere of what endures, not so much the moment of discovery[6].

This recursive pattern is an insight into the ways in which humans have adapted through generations: our inventions compel us as much as serve us. There is a demand that we inhabit the systems our inventions create, that we adapt to them, change our rhythms and structures to fit their existence. Artificial intelligence will be no exception. It is already changing the solutions we attempt, and the problems we imagine. Once embedded, it will not feel like an addition, it will feel like the clock, or electricity, or the wheel.

III. Adaptation as Dislocation

This pattern of recursive adaptation carries costs that we don’t see until after we have embraced change. The clock gave us punctuality, but it detached life from the slow drift of the seasons and the motion of the sun. The press spread literacy, but also spread heresies and pamphlets of hate. The radio gave companionship to the isolated, but it also allowed propaganda into every household. The internet granted access to vast acres of knowledge, but it shouts at us with a million voices such that knowledge itself becomes hard to discern. Each invention created a path, but closed another. Each forced us to adapt and survive inside the worlds we had created, adjusting each other to structures we did not foresee.

And with artificial intelligence, the precipice may be steeper. For the first time, this tool is not just an extension of our hands or the eyes, but of thinking and reasoning. The plough extended muscle, the telescope extended sight, the computer extended calculation. But machine learning grasps at judgment, inference, and even imagination. This technology unsettles what we do, but also forces us to change how we come to think. We will adapt, because adaptation is our constant, but the question we have to ask is “What recursive adaptation are we willing to make by outsourcing reflection?”

IV. Uneven Futures

Adaptation, while a constant in human history, is never uniform. The literate elite of the 15th century thrived while the peasantry remained oral, and watched the written word pass them by. The industrial revolution enriched industrialists and inventors, and broke the bodies of workers, turning villages into slums and trades into servitude. The digital revolution widened the gap between those fluent in code and those left voiceless before the machine. This created a new group of middlemen who spoke the language of systems while others became invisible inside them. Each time the wheel turned it has lifted some and discarded others[7].

Artificial intelligence promises the same. It will become a power tool in the hands of those who know how to utilise it, extending their reach, and accelerating their designs. For others, skills long mastered become obsolete, roles hollowed out, identities connected to tasks that no longer exist. What was once a source of pride becomes an empty redundancy. The self that was built around labour, finds itself displaced.

Adaptation, as constant as it is, never arrives as freedom to all. It arrives as necessity. We submit to it because it leaves us no choice. Beneath the stories of progress, there remain the quieter stories of those who adapt only by losing.

V. The Second Recognition

If the first recognition of coexistence is that we cannot abandon invention, the second is that humanity endures by reshaping itself to survive what it has made. We are creatures of nature, shaped by invention, and our history is a long record of bending to environments of our own design. Cities changed how families lived and related, markets changed how goods were traded, machines changed how people worked, and networks made distance less important. Each invention was an instrument, but it was also a condition, and each change required us to learn different ways of being human.

Living with artificial intelligence will be the same. The question is not if we will adapt but what kind of humans we will become when we do. Will we be lessened by the burdens we relinquish or remade into an entity yet unnamed? History does not guarantee balance, only the knowledge that survival demands submission to the shape of something new.

[ARCHIVE FOOTER – TRANSLATION SUMMARY]

Integrity of fragment: 0.81

Recovered sections: 13 of 25

Anomalies detected: [redacted]

Notes: Residual formatting artefacts removed during reconstruction.

Annotations (Recovered 2237)

Source References

Original Link: What Separates Humans From Animals According To Aristotle?

Archive Snapshot: Internet Archive ↩︎[L] - The repeated use of "we" and the metaphor of "breathing" in a self-created "atmosphere" suggest that the author is reluctantly intimate with the machine of adaption. They sound resigned but clear, knowing that adapting now feels like agreeing to be trapped. This is not triumphant humanism. ↩︎

Mumford, Lewis. Technics and Civilization. United Kingdom: University of Chicago Press, 2010. ↩︎

Does Technology Drive History? The Dilemma of Technological Determinism. United Kingdom: MIT Press, 1994. ↩︎

Edgerton, David. The shock of the old : technology and global history since 1900. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2007. ↩︎

[L] - Focussing on "endures" instead of "discovery" shows a personality that is more interested in long-term effects than in short-term excitement, like a historian's patience than an inventor's thrill. The choice of words puts "spark" on the back burner in favour of the slow pressure of use. This shows that the author is tired of hype and prefers the long-term responsibility of adoption. ↩︎

[L] - The phrase "Lifted... discarded" has a cadence that fits with grief; the author is not neutral about who benefits from adaptation. The previous image of "middlemen who spoke the language of systems" presents harm as linguistic exclusion, suggesting apprehension regarding the authority to interpret reality. This voice sounds like someone who has seen the wheel turn enough times to not trust promises of evenness, but still keeps track of the losses so they do not go away. ↩︎