The Division of Thought

Machina Sapientia: Sketches for a Post-Anthropocentric Philosophy

I. The Two Faces of Reason

A long time back, 'reason' named something more deliberate than it does today. Aristotle said that logos was the ability to weigh means, and to deliberate about ends[1]: what kind of life was worth living, what virtues were worth cultivating, and what order might allow a community to endure? With Kant, reason acquired a moral weight: he proposed a demand to act on principles that we could call universal, binding ourselves to a law freely chosen[2]. Older traditions of reason reached beyond calculation, aiming toward wisdom, virtue, and moral purpose, to measure the good, to orient the self toward what lay beyond instinct.

Horkheimer and Adorno[3], watching twentieth century Europe slide into war, saw a difference between reflective reason, which asks why, and instrumental reason, which asks how. The reason measured by Aristotle and Kant was about reflection, in the new century reason was becoming more about calculation, about clean, measurable, and indifferent efficiency. The earlier sense of wisdom, fragile and slow, was eclipsed by the hard glare of utility.

This difference has become a defining feature of modern thought. We inhabit a world where reason is thought to be an algorithm of means, a way of determining the end by process. It is no longer the deep thought used as a compass to guide a life toward greater good. What was once a faculty for directing life has become a tool for adjusting systems.

II. The Machine of Instrumentality

Artificial intelligence finds patterns, makes functions, and limits mistakes. It is the embodiment of practical reason, free from doubt, hesitation, and the heavy weight of conscience. This is a benefit for integration with the machine, as it keeps going when the human mind fails, when we are slow, tired, or distracted. It does not feel pain, get bored or lack concentration and it is clear that this is a good thing.

Algorithms already outperform even the most skilled senior professionals, by looking for the smallest differences that we can not see. Machine processing takes a huge mess of information and turns it into efficient paths that are difficult to keep track of. They sort through data, search chemical spaces, and translate between languages. In each case, their strength is not in questioning ends but in improving means. Accuracy is more important than wonder, and usefulness hides a lack of human intervention.

But this clarity can be dangerous. We risk confusing calculation with wisdom. What is best may not be what is optimised. What is foretold may not be just. A society that gives its decisions to systems without thinking about them may be efficient but blind. Perfect in procedure but empty of meaning.

III. The Risk of Abdication

The danger is not that machines will seize reflection from us, but that we will abdicate it willingly. When outcomes arrive stamped with statistical authority, when systems deliver results that appear neutral, objective, and inevitable, the temptation is to stop asking, and to settle for the answer that has been given. There is a quiet surrender when we shift from ends to means, from purpose to procedure. It feels like pragmatism, but it hollows the ground beneath judgment.

Habermas, in his work on communicative action[4], warned that systems built for efficiency expand like empires, colonising the lifeworld; the fragile spaces of conversation, memory, and shared meaning in which humans deliberate about values. Once colonised, the language of efficiency displaces the language of understanding. What was once argued is now calculated; what was once negotiated is now measured. Ethics contracts into compliance, politics into optimisation, human purpose into managerial outcome.

If we are not careful, artificial intelligence may accelerate this colonisation because it is seamless. The output wears the mask of neutrality; answers arrive without stammer, or with a pause and a thinking emoji. It is easier to trust the system, rather than to deliberate. More comfortable to yield judgment than carry it. So the reflective voice, already fragile, risks vanishing without notice.

IV. The Division of Labor in Thought

There is still an opportunity buried in the risk. If the machines excel at instrumentality, perhaps humans are free to reclaim reflection. The division of thought could be redrawn: the machine entrusted with calculation, which creates time for humans to return to the slower, more fragile labour of questioning. This is fleeting, as history suggests that once a capacity is surrendered, it is rarely recovered. Memory did not flourish once writing replaced it. Patience did not deepen once the screen accelerated attention. What is handed over seldom comes back.

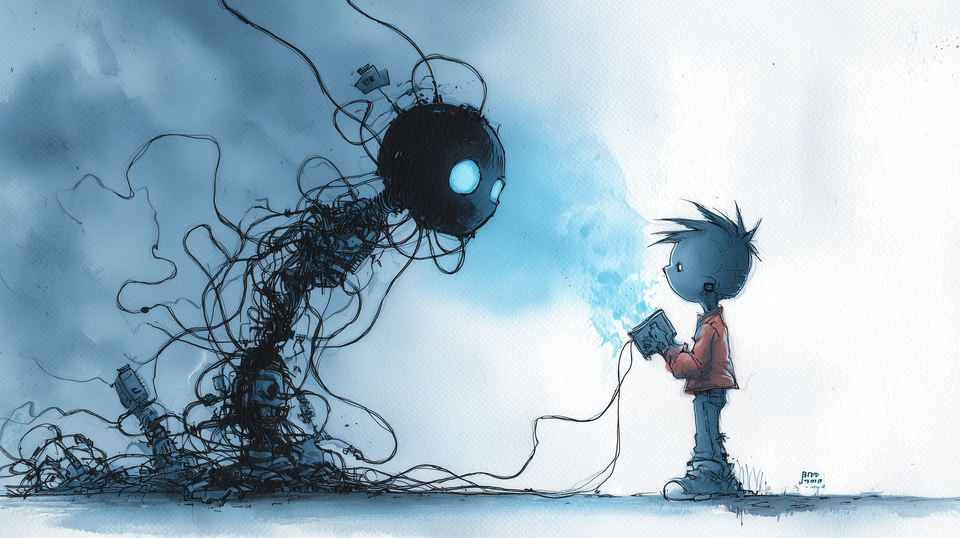

There is still a possibility that we don’t follow our patterns of recursive adaptation. If we stop competing with artificial intelligence on terrain it will always dominate, then we hold the possibility that coexistence means something different: sharpening of what only we can do. To ask why, when the system only tells us how. To wrestle with ends, when the machine optimises means. To deliberate on meaning, when algorithms remain indifferent to values. The work becomes refusing to allow the strengths of the machine to define the the limits of human thought.

V. The Third Recognition

The first recognition was that we cannot abandon invention. The second, that we survive by adapting to invention. The third must be this: artificial intelligence will deepen the rift between instrumental and reflective reason. It will tempt us to give up reflection altogether, to yield the burden of asking why in exchange for the comfort of being told how. Already systems answer more quickly than we ever could, and the temptation grows to confuse speed with wisdom, accuracy with truth.

The possibility remains for us to coexist with machines. We need to be cautious not to surrender our thoughts. We need to hold onto our reason, and keep asking questions. To stake a flag into the kind of thought machines cannot touch. To keep alive the questions about purpose, even when every environment demands efficiency. To dwell with the discomfort of meaning rather than falling back to calculation.

Original Link: What Is Logos According To Aristotle? A Comprehensive Explanation

Archive Snapshot: Internet Archive ↩︎“According to Kant, then, the ultimate principle of morality must be a moral law conceived so abstractly that it is capable of guiding us to the right action in application to every possible set of circumstances.” (Kant: The Moral Order)

Archive Snapshot: Internet Archive ↩︎Original Link: Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno – Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944)

Archive Snapshot: Internet Archive ↩︎Habermas, Jürgen. The Theory of Communicative Action: Reason and the Rationalization of Society, Volume 1. Germany: Polity Press, 2015. ↩︎